Without an independent system operator and with a rapidly changing resource mix, the US Pacific Northwest is exposed to risks that became painfully clear during the MLK 2024 Arctic Blast. That event pushed the grid to its limits and revealed structural weaknesses that have only deepened since.

Now, staring down the 2025-2026 volatile winter forecast, grid planners across the West are preparing for colder, longer-lasting, and more geographically widespread weather systems. Nowhere is that concern more urgent than in the Pacific Northwest.

According to E3’s Resource Adequacy and the Energy Transition in the Pacific Northwest: Phase 1 Results, the region could face the possibility of a 6 GW shortfall in extreme conditions this upcoming winter, growing to a nearly 9 GW resource gap by 2030.

With accelerating load growth, tightening transmission constraints, and major thermal retirements, the Northwest is entering the most challenging decade for reliability in its modern history.

Although the factors differ across regions, the Pacific Northwest’s shortfall is likely to be the first of many such situations across the continent as shrinking supply collides with growing demand.

Supply-Demand Gap Opens in 2026 and Widens Quickly

E3’s modeling shows that accelerated load growth and continued retirements combine to create a resource gap beginning in 2026, expanding to about 9 GW by 2030. Clean resources such as wind, solar, and batteries—while valuable for decarbonization—make relatively small contributions to meeting winter resource adequacy needs.

Meanwhile, the pace of project development continues to be slowed by permitting delays, interconnection backlogs, federal policy uncertainty, and rising costs. The result is a growing mismatch between when the region needs new capacity and when that capacity can realistically be built.

Transmission Constraints Make Matters Worse

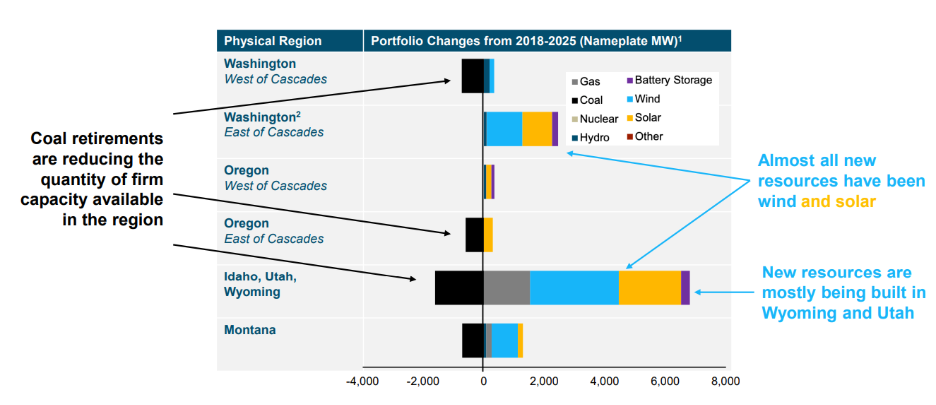

Resource challenges aren’t just about what gets built—they’re about where it gets built.

Between 2018 and 2025, most new generation in the broader Northwest came online in Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah, adding around 7 GW of nameplate capacity while retiring just over 1 GW of coal. In contrast, western Washington saw about half a gigawatt of retirements with less than half a gigawatt of new additions. Eastern Washington fared better in terms of nameplate growth, but most of that growth came from wind and solar—resources that provide limited firm capacity in the winter.

Even worse, the longstanding transmission bottlenecks across the Cascades make it extremely difficult to move that energy westward during critical events. Those same constraints limit the region’s ability to import from the Rocky Mountain states as well.

In practice, the east-to-west paths are already heavily loaded under normal conditions, and most of the high-voltage lines that cross the mountains were never designed to carry the massive amounts of new wind and solar expected to come online in the next decade.

Bonneville’s own studies show billions of dollars in upgrades would be needed just to accommodate queued renewable projects east of the Cascades, and even then, congestion on major north–south and east–west corridors would remain a persistent operational challenge.

In short: even when resources exist on paper, they may not be deliverable when the system is stressed.

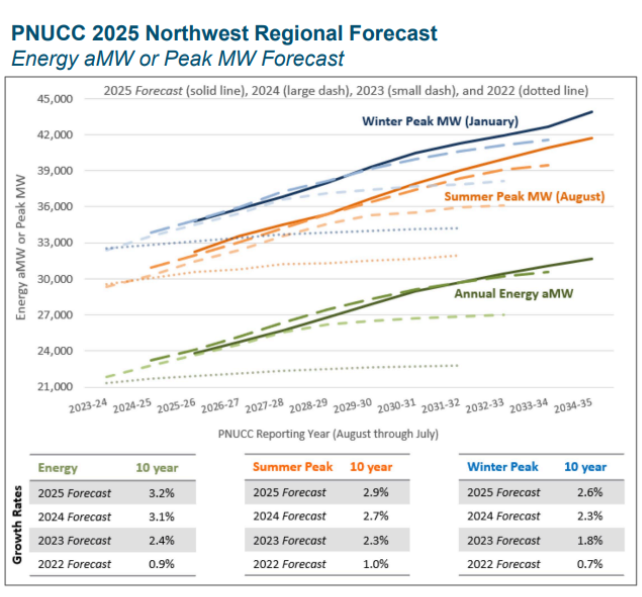

Demand Is Rising Faster Than Expected

While supply tightens, demand is growing—faster than utilities had projected just a few years ago. Factors driving load growth include:

- Higher-than-expected AC adoption following recent heat waves

- Policy-driven EV adoption

- Population growth and new building construction

- A surge of new data center interconnections

Energy efficiency offsets a portion of this growth, but not nearly enough. PNUCC’s 10-year peak forecast has risen sharply over the past four years. In 2022, summer peak growth was projected at roughly 1% per year; by 2025, that projection had nearly tripled. Winter peak growth saw a doubling. The upward revision underscores how quickly the region’s demand outlook is changing.

Not Nearly Enough New Capacity Is Coming

E3 estimates that the Northwest will need roughly 9 GW of new capacity by 2030. Yet the active development pipeline accounts for only about 3 GW—and even that number relies heavily on coal-to-gas conversions and hydro upgrades.

To meet the pace of growth envisioned in utility IRPs, the region would need to build resources at four to five times the historical rate. There is no evidence yet that this ramp-up is happening.

Grid Vulnerability During Cold Spells

The region’s vulnerability to extended cold spells is well documented. Most loss-of-load events in the Northwest occur in the coldest winter months and last more than 50 hours; some exceed 100 hours. For context, Winter Storm Uri’s outages in Texas lasted 96 hours.

The MLK 2024 event reinforced these concerns—wind production was extremely low across multiple balancing authorities. Bonneville Power saw near-zero wind generation from January 15–17 and again from January 19-21. NorthWestern Energy saw almost no wind from January 12–14. Solar contributes little during Northwest winters, and hydro availability is increasingly variable. The retirements of firm thermal units only deepen the exposure.

California’s massive planned solar and storage build-out—50 GW by 2035 and 100 GW by 2040—provides little relief. Those resources are well suited for a summer-peaking system, not a winter-peaking one, and transmission constraints limit northbound support during extreme cold.

Structural Challenges Identified by E3

E3 outlines three overarching barriers:

- Transmission access is physically and institutionally constrained.

Procurement and transmission planning are misaligned, firm transmission rights are scarce, and siting remains difficult.

- Capacity accreditation remains uncertain.

The Western Resource Adequacy Program (WRAP), recently introduced across utilities in the Northwest to help with supply constraints, is still voluntary and nonbinding, and accreditation methods for winter-peaking systems are in flux.

- New firm capacity is difficult to develop.

Most clean resources provide limited resource adequacy (RA) value. Clean firm technologies are not yet widely commercial, and natural gas—currently the only scalable near-term firm option—is politically difficult to site and lengthy to build.

What Industry Leaders Are Saying

At the October Regional Energy Symposium in Portland, industry leaders highlighted the urgent need for better gas-electric coordination, prompted in part by the Jackson Prairie natural gas storage outage during MLK 2024. Speakers emphasized that cold-weather events are becoming “broader, deeper, and longer,” requiring new operational and planning strategies.

NERC President and CEO Jim Robb pointed to three drivers of the evolving shortfall:

- The rapid transformation of the grid,

- Replacement of coal with variable renewables, and

- Increasingly severe and persistent extreme weather

The underlying message was clear: the region’s traditional planning assumptions no longer hold.

Demand Response: Useful but Insufficient

The Northwest needs an RA tool it can scale quickly, and demand response (DR) is one of the fastest options available. It provides an essential short-term pressure release valve, but it cannot close a multi-gigawatt structural capacity gap.

NERC’s latest Winter Reliability Assessment shows that across the entire bulk power system, 8 GW of new demand response has come online since last winter—making it one of the largest contributors to new winter peak resources, second only to batteries. That growth reflects how heavily regions are leaning on DR to navigate rising winter peaks in the face of slow thermal additions and declining accredited wind capacity.

The same dynamic is playing out in the West. In areas like the WECC Basin, NERC notes that controllable DR has doubled year over year, helping offset rising internal demand. But even with that expansion, both the Basin and the Northwest remain exposed during the kinds of extreme winter events that drive most loss-of-load risk—when thermal derates stack up, gas supply tightens, wind output collapses, and imports may not be available.

Demand response can meaningfully soften peak conditions over the next few winters, giving operators more room to maneuver during tight hours. But its limitations are clear: DR is bound by event-hour constraints and becomes less dependable during long-duration cold spells, the very scenarios that strain the Northwest the most.

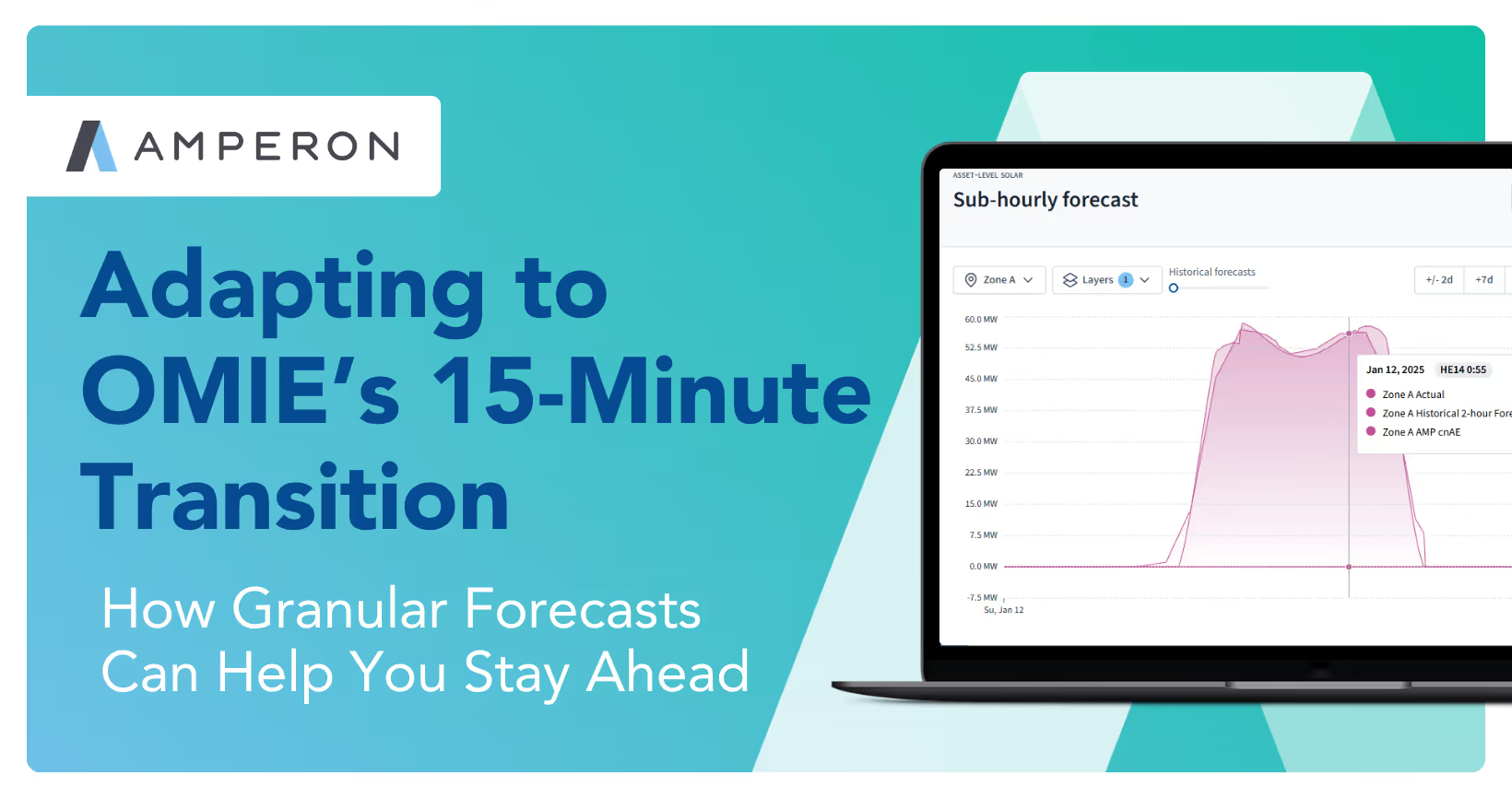

Where Grid Forecasting Helps with Resource Adequacy

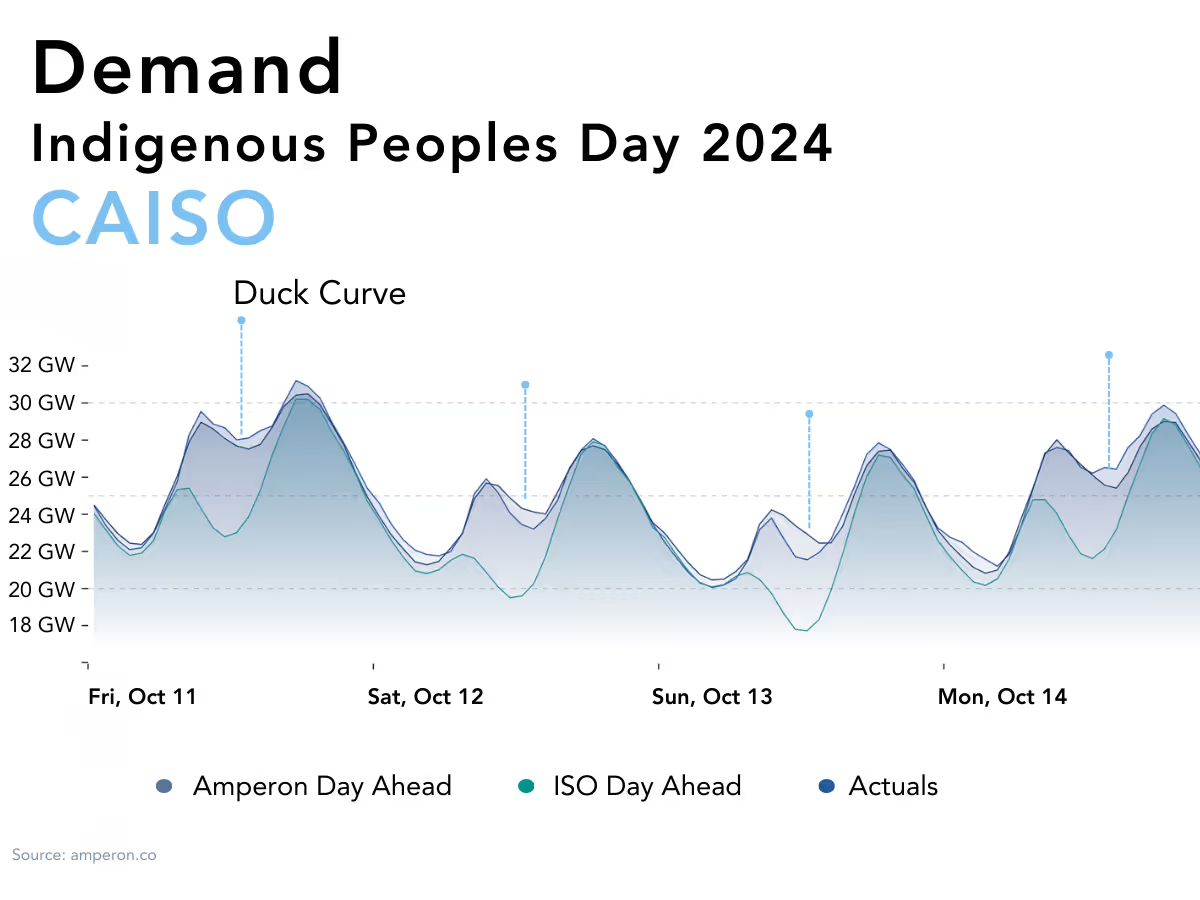

While the long-term solution requires major infrastructure development and better regional coordination, the MLK event underscored a separate and more immediate need: better visibility into impending conditions. The window of time when Arctic events develop is exactly when utilities, balancing authorities, and regional operators need sharper insight into future load and renewable output.

Improved utility-level load forecasting and asset-level renewable forecasting won’t close a 9 GW resource gap, but they do help operators prepare, pre-position resources, and coordinate across gas and electric systems more effectively. In a region facing tight margins for the foreseeable future, situational awareness is one of the most practical tools available to reduce operational risk.

.svg)

%20(3).png)

%20(2).png)

%20(1).png)

.png)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(15).avif)

.avif)

%20(10).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)