In the world of energy markets and power systems, forecasting has always played a central role. Traditionally, most forecasts have been delivered as single numbers—a predicted demand at 5 p.m., or the expected price in the day-ahead market—and these point forecasts have shaped everything from generation scheduling to trading strategies.

Behind the scenes, those numbers were typically produced using deterministic forecasting approaches: a single set of assumptions, inputs, and model logic yielding a single expected outcome.

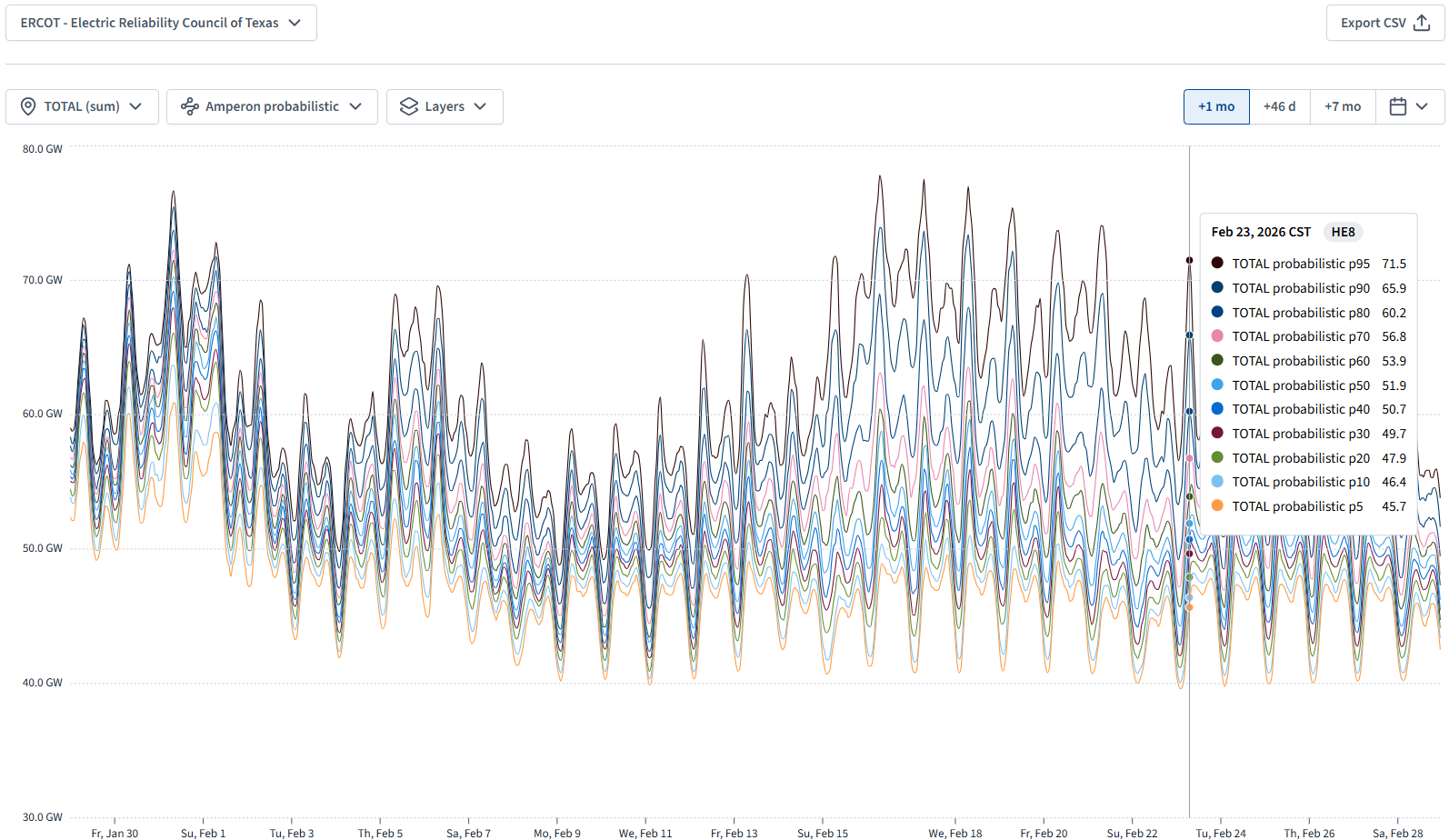

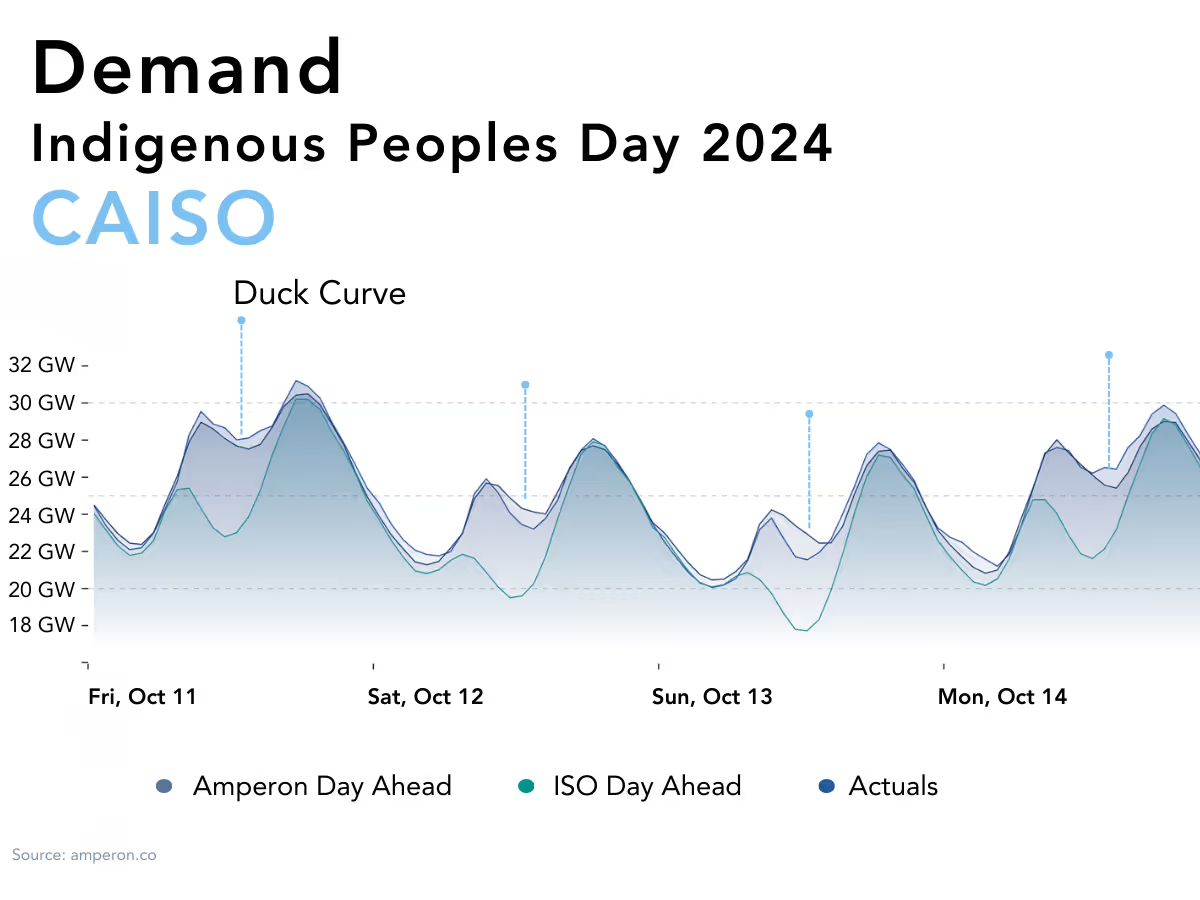

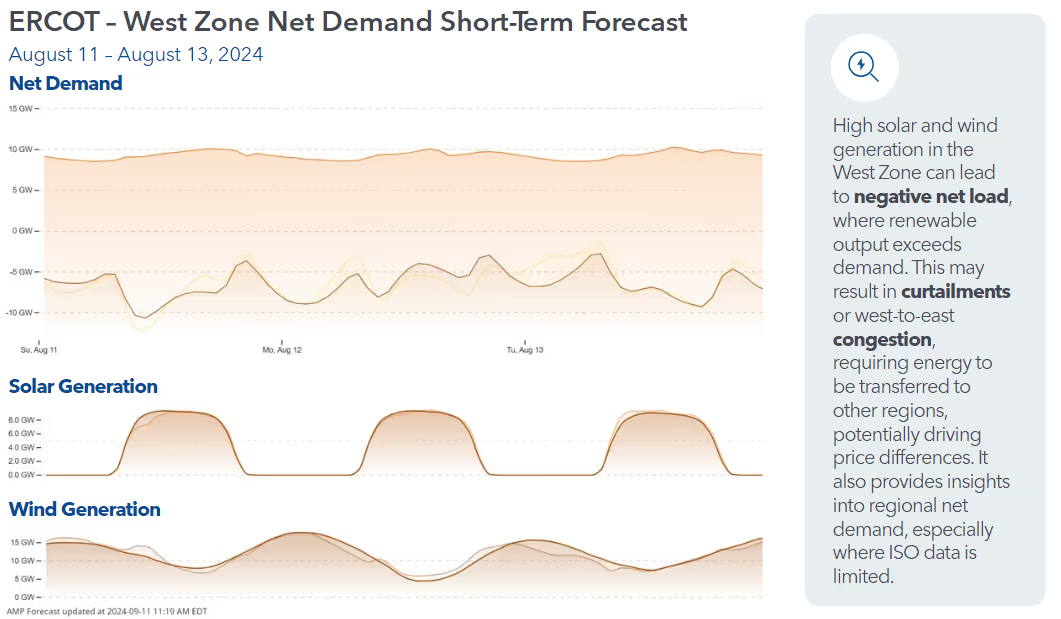

As solar generation has reshaped net demand profiles, familiar reference points have shifted. Peaks now occur later in the evening and with greater uncertainty than before. Operational and market decisions must account for variability, relying on forecasts that describe a range of possible outcomes rather than a single expected value.

What this reflects is not a failure of forecasting, but a broader shift in its role—from producing answers to supporting decisions made under risk.

Point Forecasts and Deterministic Models

For years, highly accurate point forecasts have been the standard measure of success. Even as energy systems have grown more complex and variable, deterministic forecasting methods that produce a single best estimate remain the dominant way information is generated, communicated, and evaluated.

Point forecasts are easy to interpret, straightforward to communicate, and simple to assess. In systems where variability is limited and uncertainty manageable, this works well. Forecast quality can be judged by how close a single predicted value came to the realized outcome.

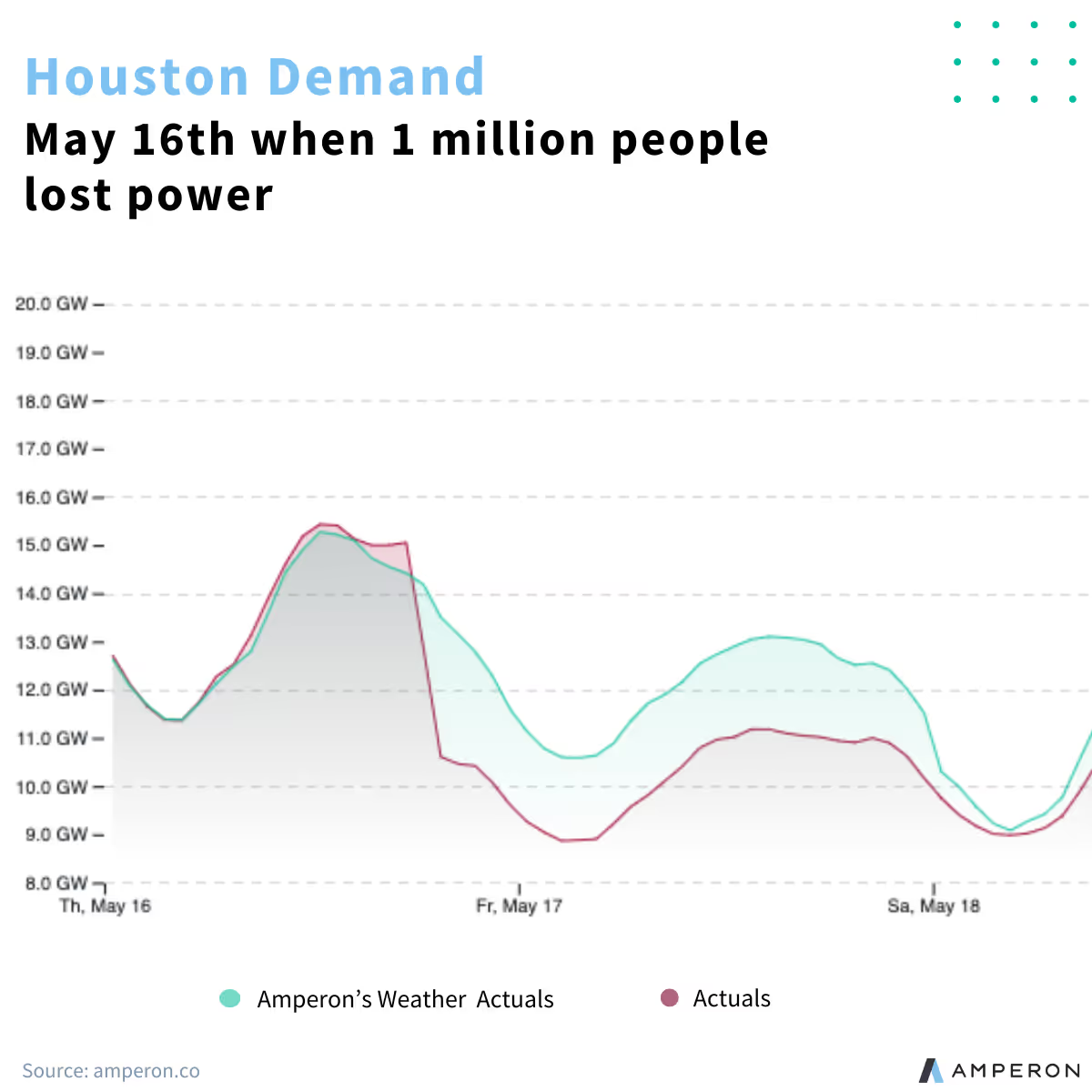

However, as conditions have changed, the limitations of relying solely on deterministic point forecasts have become more apparent. Two forecasts can produce the same point estimate while implying very different levels of risk—a distinction that deterministic models fail to make explicit.

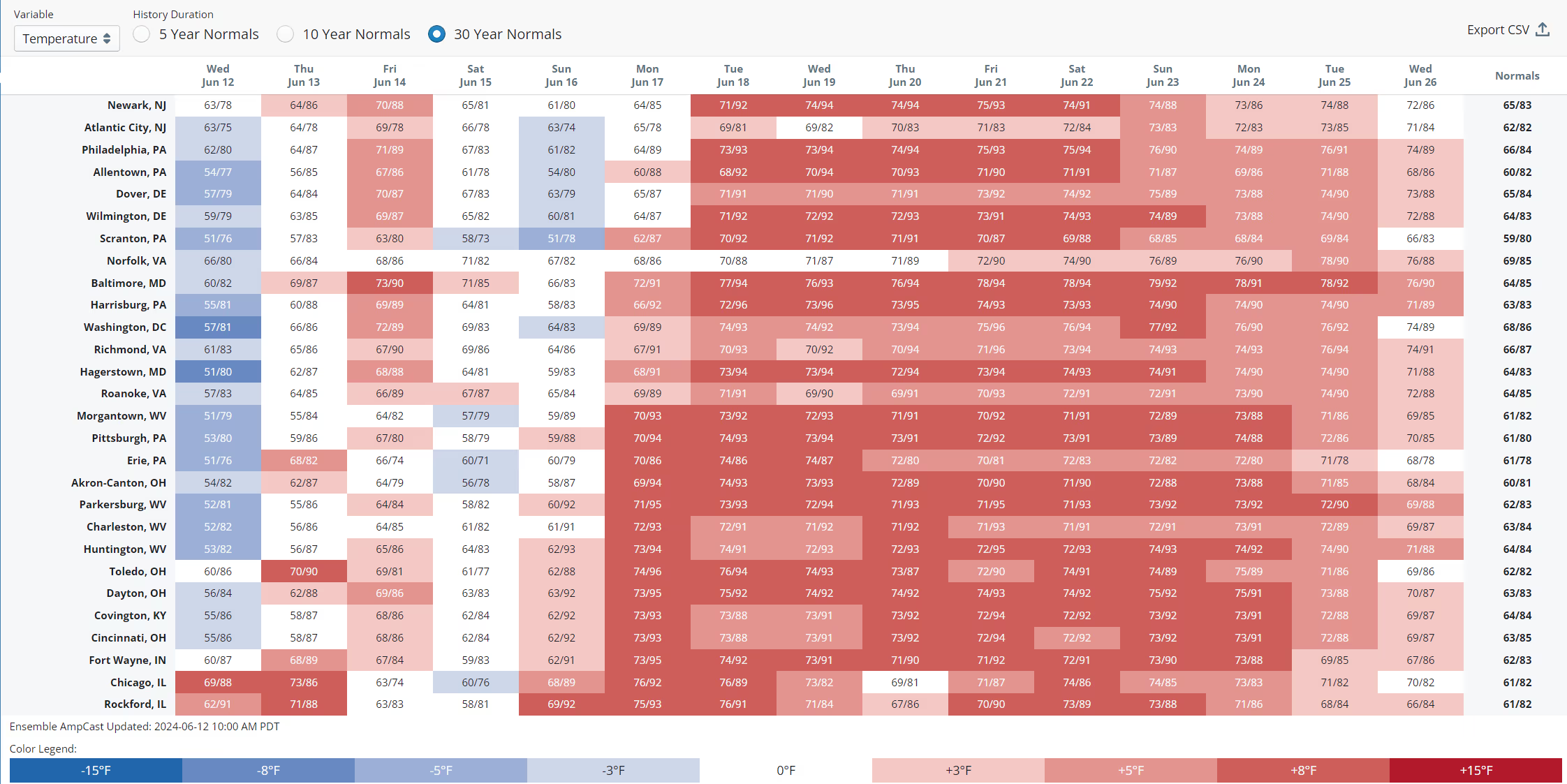

Imagine two day-ahead demand forecasts, both calling for 32 GW. On the surface, they are indistinguishable: same number, same confidence, same green checkmark on the dashboard. But the stories behind them could not be more different.

In one case, the forecast reflects a cool spring day with steady temperatures and predictable behavior. In the other, 32 GW sits at the center of a developing heatwave, where a one-degree temperature miss could swing demand by gigawatts and push the system toward its limits.

The point forecast is identical. The risk is not. In practice, that missing context is often managed through extra reserves, operator intuition, and last-minute interventions when reality refuses to follow the single line drawn the day before.

What has changed is not the importance of grid forecasting, but the complexity and consequences of the decisions it informs, where insight into the most likely outcome is strengthened by additional information about uncertainty and risk.

What has changed is not the importance of grid forecasting, but the complexity and consequences of the decisions it inform.

A Generational Shift in Energy Forecasting

Several forces have reshaped both how forecasts are produced and how they are used. Most notably, the rapid growth of wind and solar generation has increased exposure to weather-driven variability on every time scale. Extended periods of unexpected weather now cause major headaches for market participants.

Meanwhile, changes in consumer behavior—such as demand response programs, electric vehicle charging, and other flexible loads—have added additional, non-weather-driven uncertainty.

At the same time, richer and faster data such as higher-resolution weather inputs, real-time asset measurements, and more granular market signals have expanded what forecasters can observe. Advances in modeling from ensemble techniques to machine learning and hybrid physical-statistical approaches have further improved forecast performance.

Together, these developments have made uncertainty more visible. Rather than eliminating variability, better data and models have revealed how structurally embedded it is in modern energy systems.

As a result, expectations have begun to shift. Forecast users are increasingly asking not just what is most likely, but what else is possible and how likely those alternatives might be.

Forecast users are increasingly asking not just what is most likely, but what else is possible and how likely those alternatives might be.

The Natural Evolution Toward Probabilistic Forecasting

In response to these changes, probabilistic forecasting has emerged as a natural evolution of deterministic approaches. Instead of producing only a single outcome, probabilistic methods describe a range of plausible futures and associate likelihoods with them.

Importantly, this does not eliminate point forecasts; it places them in context. Probabilistic forecasts can answer a broader set of questions:

- How wide is the range of possible outcomes?

- How confident should we be in any given estimate?

- Where are the downside and upside risks?

- How much is at risk if I’m wrong?

Rather than replacing deterministic forecasts, probabilistic forecasting builds on them by making uncertainty explicit and usable.

Rather than replacing deterministic forecasts, probabilistic forecasting builds on them by making uncertainty explicit and usable.

From Hype to Reality: Probabilistic Forecasting Evolves from Concept to Capability

Probabilistic forecasting has traditionally been discussed more than it was deployed. While the underlying methods were well established, practical adoption lagged. Generating calibrated forecasts that went beyond single numbers to provide reliable estimates of what could actually happen, while presenting them in ways that fit existing workflows, posed real challenges.

Those barriers have steadily fallen. Advances in data infrastructure, computational power, and modeling techniques have made probabilistic forecasts operationally viable. At the same time, decision makers have become more comfortable incorporating risk-based information into planning, trading, and operations.

As a result, probabilistic forecasting is moving from an emerging idea toward a foundational capability, even as deterministic point forecasts remain the primary interface for many decisions today.

Where Grid Demand and Asset Generation Forecasting Are Headed

Forecasting is moving beyond static predictions. Today, it is about providing insights that embrace uncertainty and support better decisions. Accuracy continues to be essential, but forecasts are increasingly valued for how well they capture variability, risk, and the full range of possible outcomes.

Deterministic forecasts and point estimates remain important—they are often the starting point for action. But modern forecasting methods are designed to reflect the inherent uncertainty of today’s energy systems. Probabilistic forecasting is not a distant goal; it is already here.

The shift in forecasting mirrors the changes in the energy system itself. As volatility and complexity have grown, forecasts have expanded their role—from offering a single expected value to showing the range of outcomes that matter for decision making.

Probabilistic forecasting responds to this change. Not to eliminate uncertainty, but to make it understandable, communicable, and actionable. By embracing this approach, decision-makers can navigate an increasingly uncertain energy future with confidence, supported by forecasts that reflect the realities of today’s energy systems.

By embracing this approach, decision-makers can navigate an increasingly uncertain energy future with confidence.

.svg)

%20(3).png)

%20(2).png)

%20(1).png)

.png)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(15).avif)

.avif)

%20(10).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)